Egypt's dozen uselessly brutal years

Plus, a new MENA Academy roundup

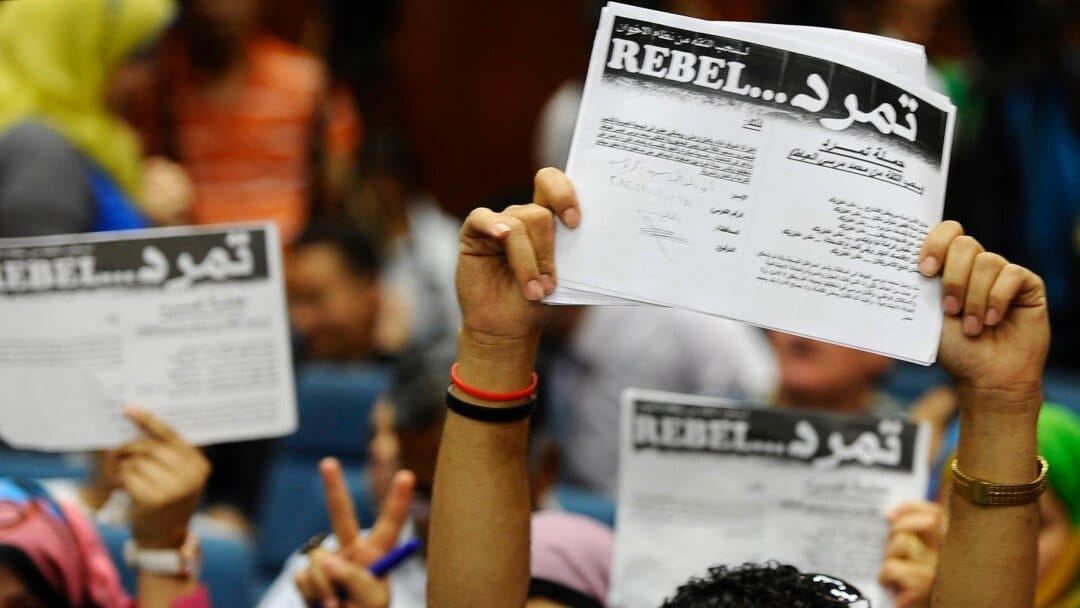

Twelve years ago today, huge crowds took to the streets in Egypt demanding that President Mohammed el-Morsi step down from office. The Tamarod June 30 protests were not, as claimed at the time, the biggest democratic uprising in history, but they were big. They were not fully autonomous, given the now widely reported UAE and other external funding and support for the movement as well as the quiet support behind the scenes from the military and other security services, but many people clearly felt their demands deeply. On July 3, General Abdelfattah el-Sisi carried out a textbook military coup, removing Morsi from office and establishing a new and depressingly enduring military regime. At the time, there was an exceptionally intense political argument about whether Sisi's coup had actually been a coup (the Obama administration never called it what it was); twelve years of brutal authoritiarian military rule later, those arguments have long since faded into embarrassed silence.

At the time, fear and hatred of the Muslim Brotherhood, inflamed by highly polarized social media and satellite television broadcasts as well as deterioriating conditions on the ground, led a lot of people to be willing to accept the military as their savior. Perhaps they were overly confident that the mobilized public would always be able to rise up against the military if it failed to restory democracy. Perhaps they just preferred what they knew of military rule over what they feared about Muslim Brotherhood rule. Either way, the hopes that June 30 and the military coup might pave the way for a return to democracy gave way all too quickly to the military's August 6 Rabaa massacre of more than 1000 Islamist protestors in broad daylight in central Cairo – still a shocking crime against humanity even in the wake of the horrors of Syria and Sudan, still an appalling moment of impunity even in the wake of Israel's genocide in Gaza.

Sisi's survival and ability to etrench a new form of military rule through populist nationalist rhetoric and brutal repression, despite presiding over endemic economic crisis and the systematic crushing of democratic civil society, has been an unfortunate template for the restoration of Arab autocracy. It's a grim reminder to activists and political scientists that, too often, repression works in the short term – and that too often, people willingly give away their freedoms out of fear or cultivated hatreds. It's sparked an important wave of new literature on autocratic restoration and revolutionary failure that I wish had never had to be written. And it has done so much to crush hope and derail even the idea of the possibility of positive change far beyond Egypt. No wonder Trump called Sisi his favorite dictator.

It's sobering to realize that Sisi has now ruled Egypt longer than Anwar Sadat. Sadat, for all of his failings, presided over epochal changes in Egypt's political and economic history: launching and in many ways winning the 1973 war; doggedly pursuing peace negotiations in the aftermath, culminating in his signing the Camp David Accords which returned the Sinai to Egypt, sold out Palestinian rights, and guaranteed Israeli security for going on 45 years; shifting Egypt from the Soviet camp into a core US regional ally; opening up the economy with neoliberal reforms which created the conditions for the emergence of a crony capitalist class and stripped away so much from the poor and middle class; and oversaw the re-emergence of the Muslim Brotherhood and Islamist movements as a counterbalance to Nasserists and the Left. What has Sisi accomplished in a dozen years besides staying in power?

Here's some of the best reads about Egypt under Sisi. Maged Mandour's 2024 book Egypt Under Sisi describes "a militarized, repressive, mobilized and brittle regime." Mona el-Ghobashy's 2022 Bread and Freedom is one of the very best accounts to date of the 2011 revolution and its highly contingent path. Jannis Julien Grimm's Contested Legacies focuses directly on the Rabaa massacre and the politics of its aftermath and its legacy (I wrote about Ghobashy and Grimm together in this review essay.) Neil Ketchley’s Egypt in a Time of Revolution and Amy Austin Holmes’s Coups and Revolutions both look at the drivers and the aftermath of 2013. Walter Armbrust's Martyrs and Tricksters offers a novel account of Sisi's political role and the defeat of Egypt's revolution. Nathan Brown, Shimaa Hatab and Amr al-Adly's Lumbering State, Restless Society situates Sisi within a much longer trajectory of Egyptian political history. Atef Shahat Said's Revolution Squared focuses on the "lived contingencies" of Egypt's revolutionaries through the 2011 and 2013 uprisings and beyond. Hesham Sallam had a nice overview of Sisi's first decade. And finally, Yezid Sayigh's "Egypt's Second Republic" mercilessly dissects the political economy of "a new republic defined by a social ethos of “nothing for free,” a new form of state capitalism, and hyperpresidential powers set within a military guardianship that secures his regime but leaves it unable to resolve political, economic, and social challenges."

Meanwhile in the MENA Academy

It's been a while since we rounded up interesting new publications in academic journals. So here's something to start your week, once you've finished reading up on Egypt. We first turn a spotlight onto some outstanding recent publications on gender: the new issue of Middle East Report, Hind Ahmed Zaki's article on deveiling in Tunisia, and Balsam Mustafa's article on gender politics in Iraq. We then note a new special issue of Middle East Law and Governance on populism in the Middle East. Finally, we present three important articles on Syria and Lebanon – Emily Scott on refugee NGOs, Marika Sosnowski on the Syrian insurgency's development of alternative bureaucratic forms, and Kelly Stedem on security provision in Lebanon. We conclude with Marine Poirier's article on the rehabilitation of Mubarak-era elites in Sisi's Egypt. Enjoy!

Middle East Report 314 "New Gender Frontlines" edited by Sabiha Allouche, Fida Adely and Hesham Sallam. ABSTRACT: takes stock of the role gender plays in the present political moment—one of ongoing genocidal war, US repression of political dissent and border violence. The issue borrows its title from a 2013 issue of Middle East Report (268), which explored the relationship between gender and revolution during and immediately after the popular uprisings. More than 10 years later, women and men across the region are confronted with the consolidation of nation states, resurgence of counterrevolutionary violence and hardening of borders. Now, as then, our contributors make clear that gender is not incidental but central to political organizing and participation, violence and resistance and the textures of everyday life. As the roundtable with Deniz Kandiyoti, Judith Tucker, Mounira Charrad and Suad Joseph reveals, questions of state power have always been marked by gender, class and other differences. The rest of our contributors take up these analytical tools, asking what gender can tell us about political mobilization in Sudan, genocidal violence in Gaza, deportation regimes in Turkey and the United States, emergent masculinities in Syria, democratic politics in Iran and more. What emerges are today’s gender frontlines—sites of violence but also spaces of struggle and imagination.

Hind Ahmed Zaki, "Veiled transgressions: revisiting Tunisia’s secular/religious binary through the afterlives of the hijab ban," International Feminist Journal of Politics (June 2025). ABSTRACT: This article analyzes the efforts of Tunisian women to frame the hijab (veil) ban under the former autocratic regime of Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, also known as Circular 108, as a women’s rights violation through mobilizing Tunisia’s process of transitional justice. Based on fieldwork research including 40 in-depth interviews with ordinary women and ethnographic observation of the work of the Truth and Dignity Commission, this article contributes to scholarship on feminist politics in post-revolutionary Tunisia in three ways. First, it documents the complex terrain of women’s repertoires of resistance to Circular 108, demonstrating how their lived experiences trouble Tunisia’s official narratives of state-sponsored feminism by highlighting how Circular 108 oppressed thousands of Tunisian women. Second, the article shows how the hijab ban and its contemporary afterlives reveal an intricate web of patriarchal domains that affect women’s decisions to veil or not, including the family, local communities, the state, and its main opposition, political Islamic movements. Third, the findings directly challenge the secular/religious conceptual binary that dominated earlier scholarship on women’s rights in post-revolutionary Tunisia, confirming the need – emphasized by recent studies – for more nuanced analyses of the politics of the veil in the Middle East and North Africa.

Balsam Mustafa, "Gender found Guilty: Anti-Gender Backlash and (Dis)Translation Politics in Iraq," Gender and Society (June 2025). ABSTRACT: The Iraqi Federal Supreme Court banned the term gender in February 2024, resulting in a crackdown on gender equity and significantly undermining the space for feminist activism and advocacy. This article examines the conditions leading to the 2023 anti-gender backlash in Iraq, the discursive strategies of the backlashers, and its broader implications for feminist activism. The backlash was rooted in ongoing sociopolitical repression following the 2019 Tishreen (October) protests and a climate of widespread disinformation. It gained traction by weaponizing concepts of gender and homophobia. Opponents framed the term gender as a Western plot aimed at undermining Islamic values and societal norms. They exploited the problematic relationship between gender and translation, using deliberate misinterpretations to construct a narrative that demonizes gender and those who support gendered understandings of social relationships. Analyzing the backlashers’ discourse and incorporating local feminist voices, this study highlights the backlash on gendered activism, academic inquiry, and women’s rights. The article concludes by discussing the intertwined nature of discursive and material violence, emphasizing the erosion of human rights in post-2003 Iraq and contributing to the broader literature on gendered activism in the Middle East and globally.

Middle East Law and Governance has a special issue on populism in the Middle East and North Africa. Bassel Salloukh and Ammar Shamaileh introduce the issue (open access), situating the comparative and theoretical study of populism within the regional context. Hani Awad kicks it off with a conceptual tour d'horizon. Curtis Ryan examines the case of Jordan, where populism takes different forms even among the most traditionally pro-regime elites. Shaimaa Magued looks at populism in Egypt after the 2013 military coup through lens of Agamben's 'state of exception'. Mohamed Salhi writes about new forms of right-wing Moroccan nationalism manifesting in online spaces. Beatriz Tomé-Alonso, Carolina Plaza-Colodro, Nicolás Miranda, and Said Kirhlani look at populism within Morocco's Islamist PJD.

Marika Sosnowski, "The bureaucratic revolution: the Syrian opposition’s civil registry system," Third World Quarterly (June 2025). ABSTRACT: Adding to the anthropological literature on revolutions, this paper argues that the Syrian revolution should not only be seen through its violent iconography or as a lost cause but rather as an ongoing, bureaucratic process. Based on over 60 in-depth interviews with Syrian lawyers, judges, civil servants and civilians as well as with international humanitarians and legal experts, it examines the vision, hopes and legal aspirations of bureaucratic revolutionaries – lawyers and judges, administrators and civil servants – who established and implemented the Syrian opposition’s civil registry system. Using Veena Das’ idea of magic and the Arabic Islamic concept of al-ghayb (the hidden or unseen), the article highlights and unpacks the tension and co-constitutive nature of the magical, unseen vision of the revolutionary bureaucracy and its legible, rational reality. Through such a lens important insights can be gleaned about the grey zone that revolutions, and revolutionaries, beyond Syria inhabit – between legible and illegible, real and vision, a state and a state in waiting.

Emily Scott, "Negotiating for Autonomy: How Humanitarian INGOs Resisted Donors During the Syrian Refugee Response," Perspectives on Politics (June 2025). ABSTRACT: More autonomous humanitarian international nongovernmental organizations (INGOs) have greater capacity to determine who receives aid among conflict- and crisis-affected populations than their donor-following counterparts. The latter are more likely to become instruments of states seeking geostrategic influence in places like Syria and Ukraine. Drawing on more than 120 interviews with INGO and donor agency workers, 10 months of political ethnography among INGOs working with refugees in Lebanon and Jordan after the war in Syria, and content analysis of organizational documents, this article investigates the ways that INGOs secure autonomy from donors. In a theory-building exercise, it introduces the concept of negotiation experience to explain why some INGOs develop skills and strategies that allow them to resist donor demands. It also identifies some of the tactics used by experienced negotiators to do so. The findings have implications for who controls and is accountable for humanitarian policy and practice, as well as the abilities of state donors to influence humanitarian behavior. They call into question expectations that INGOs “scramble” for funds under conditions of funding scarcity.

Kelly Stedem, "What State? Political Parties and Non-State Security Provision in Lebanon," Comparative Politics (June 2025). ABSTRACT: Security is the canonical public good provided by the state to its citizens. Yet, many states are incapable or unwilling to provide security in a consistent fashion across their territory. The provision of security, order, and management of crime is a crucial “good” that parties can and do offer their constituents, resulting in widespread variation in security at the neighborhood level. What explains this variation in the provision of security and local policing by political parties? Drawing on 132 semi-structured interviews conducted during eight months of fieldwork in Lebanon, this study suggests that organizational capacity is one determinant of whether political parties step into the role of security providers. It shows that maintaining robust linkages with constituent communities and party members at the local level are necessary to coordinating security measures.

Marine Poirier, "The Stain That Stays: The Uneasy Rehabilitation of Mubarak’s Men in Postrevolutionary Egypt," Middle East Critique (June 2025). ABSTRACT: This article explores the partial and selective rehabilitation of Mubarak-era elites in post-2011 Egypt. It follows the trajectories of high-ranking figures who faced public trials, and whose reintegration into political and economic life varied greatly after the revolution’s foreclosure. Drawing on biographical case studies, the research distinguishes between rehabilitation (restoring reputation) and reintegration (restoring position), and demonstrates that while these elites’ political capital remains tainted by their proximity to Mubarak and his family, as well as by various scandals, the diversification of their activities and resources combined with their significant international connections has enabled some to gradually regain footholds within the new regime’s configuration.