Is Israel really the Middle East's hegemon?

No. Here's why... and why that's dangerous.

Israel is the new hegemon in the Middle East, argue veteran Washington Middle East hands Aaron David Miller and Steven Simon in today’s New York Times. Their argument is based on Israel’s dramatic series of military offensives across the region which have decimated the capabilities of adversaries such as Hezbollah and redrawn the rules of engagement in the region by directly striking Iran and seizing control over parts of southern Syria (and also carrying out a genocidal campaign in Gaza, let’s not forget). Even on its own terms, the argument is shaky: Israel remains highly dependent on the U.S. for military support and arms, which isn’t very hegemonic of it; it has been unable to deal with the ongoing naval blockade and occasional missile attacks by Yemen’s Houthis even with aggressive U.S. assistance; and for now it has to sit back and watch as Trump contemplates nuclear talks with Iran.

The argument for hegemony based on military superiority is helpfully countered in real time by Lawrence Freedman, writing today in Foreign Affairs:

“great powers tend to assume that their significant military superiority will quickly overwhelm opponents. This overconfidence means that they fail to appreciate the limits of military power and so set objectives that can be achieved, if at all, only through a prolonged struggle. A larger problem is that by emphasizing immediate battlefield results, they may neglect the broader elements necessary for success, such as achieving the conditions for a durable peace.”

That is about as perfect a description of current Israeli foreign policy and security thinking as you’re likely to find.

More broadly, the argument for Israeli hegemony is almost a textbook case of the misuse and abuse of the concept. Hegemony means more than military domination — it implies normative legitimacy and the general acceptance of the appropriateness of the international order. There’s a vast international relations literature — and a broader political theory literature — focused on the differences between unipolarity, primacy, domination, and hegemony. The short version is that orders based purely on domination are inherently fragile, tend to produce balancing coalitions and resistance wherever those options are available, and tend to exhaust the would-be hegemon through endless small wars and ever-expanding definitions of interest.

Israel has established a more favorable balance of power in the region, to be sure, as long as it has unlimited American backing. But it has virtually no legitimacy across the region. Its ongoing near-genocidal campaign in Gaza has long since cost it whatever admiration it might have been gaining in some quarters of the Gulf during the “Abraham Accords” era. Nobody else in the Middle East (or globally, outside of a few Western backers) sees Israel as a legitimate provider of order in the region — on the contrary, it is overwhelmingly seen as a force for disorder, destabilizing the region through its military escalations, occupation of Palestinian and Syrian territory, and the horrors of Gaza. It has no soft power, no cultural attraction, and nothing which might lead anyone in the region to accept its leadership — much less view its position as appropriate and normatively good. What Israel has, in short, is (a degree) of domination without hegemony — which, historically, is a dangerous place to be.

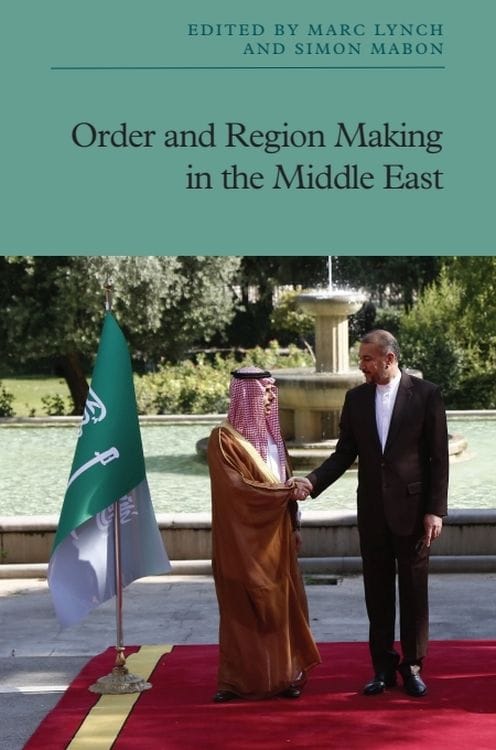

For more on the different ways of thinking theoretically about regional order and hegemony, may I suggest Order and Region Making in the Middle East, a book that I co-edited with Simon Mabon which is coming out next month? I’ll have a lot more to say about it when it is published. But for now, I’ll just tease you with the promise of a detailed and rigorous review of the various theoretical approaches to international order, and a highly original and creative group of scholars exemplifying those different approaches. It’s not a New York Times oped, but it might be a better guide to both the concept of hegemony and to where Israel really stands in the region today.

Around the MENA Academy

A few really great new journal articles about the Middle East were published since my roundup late last week. We’ve got an interesting study of the Islamist electoral advantage focused on Tunisian elections, an absolutely fascinating, rigorous, and empirically groundbreaking study of the Iranian insurgent group Mojahedin-e Khalq, and an innovative study of regional order in the Gulf. Enjoy!

Sharan Grewal, “The Islamist Advantage: The Religious Infrastructure of Electoral Victory,” British Journal of Political Science (April 2025). ABSTRACT: Why do Islamists regularly win elections in the Middle East? Why, for instance, did Ennahda perform well in every election in Tunisia’s democratic era (2011–2021)? I argue that regular interactions in mosques allow Islamists to build deeper ties and greater trust with their supporters than secular parties can. Post-election, this trust also allows Islamists to better sell their performance and justify their compromises, contributing to re-election as well. I test this infrastructure advantage in Tunisia in two ways. First, an original survey shows that mosque attendance strongly correlates with voting for Ennahda in the 2019 elections and that this correlation is driven by greater trust in Ennahda. Second, a dataset of Tunisia’s 6,000 mosques shows that sub-nationally, mosque density strongly correlated with Islamist vote share in the 2011, 2014, and 2019 elections. Overall, these results help us understand the continued victories of Islamist political parties even in contexts of poor performance.

Mohammad Ayatollahi Tabaar, “Ideological Proximity and Armed Group Competition: The Case of the Iranian Mojahedin,” Perspectives on Politics (April 2025). ABSTRACT: How does ideology affect relations between armed groups within a state? While existing research has underscored how ideological proximity can foster alliances among armed groups, this article posits that ideological proximity can also breed hostility among them. When organizations share foundational narratives, they gain access to each other’s ideational resources, which can, in turn, pose challenges to these groups’ cohesion and leadership status. These challenges manifest in the form of questioning the sincerity and authenticity of each other’s beliefs, thereby threatening the group’s survival, sometimes overshadowing the risks posed by their shared ideologically distant adversaries. Focusing on Iran’s Mojahedin-e Khalq Organization (MKO), this article highlights its evolution as one of the first armed groups to transform Islam into a potent ideology before transitioning to Marxism and later reverting to Islamism. It examines how the organization’s ideological proximity with other Islamist and Marxist actors led to conflict and outbidding violence instead of cooperation. Drawing upon a trove of the MKO’s secret documents, this article reveals how a significant portion of the rhetoric and actions of armed groups is directed at outperforming their ideologically similar rivals, rather than confronting ideologically distant adversaries.

Ruth Hanau Santini, “Securitisation and De-securitisation in the Middle East and North Africa: Relational Spatialisiation within and beyond the Gulf,” The International Spectator (April 2025). ABSTRACT: Securitisation and, more recently, de-securitisation, have characterised and shaped the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) regional space. Examples of securitisation in the 2000s and 2010s include coercive policies adopted by Saudi and Emirati kingdoms against the Islamic Republic of Iran, Iraq, Yemen and Qatar, responding either to a sectarian (anti-Shia influence) or ideological (anti-political Islam) logic. In the post-2020 regional order, these regimes’ changing regional conceptions and threat perceptions have paved the way for new diplomatic agreements contributing to regional de-securitisation. Combining Regional Security Complex theory and liberal international political economy approaches, these political and spatial shifts are illustrated through process tracing and the analysis of key strategic documents produced by Saudi and Emirati kingdoms. The analysis points to how expectations of positive trade exchanges have reduced the propensity for conflict and have acted as a further incentive for fostering trade ties as a stabilisation tool. While the volatility of the region has seemingly spiked since the 2023-24 Gaza war, leading to conflict spillover and new processes of securitisation and exclusionary spatial politics, these do not offset the parallel processes of relational spatial politics and de-securitisation initiated by Sunni Gulf monarchies since the late 2010s.

Abu Aardvark's MENA Academy is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.