The latest in Arab public opinion

This week we feature new Arab public opinion surveys, a new issue of Middle East Report, and some of the latest research from the MENA Academy. I was traveling all last week, so the Middle East Political Science Podcast will be taking a break this week.

The Arab Center recently released the Arab Opinion Index 2025, the latest iteration of its regular, massive survey of Arab public opinion – in this case involving some 40,000 face to face interviews in 15 Arab countries. The findings are especially useful because we now have nearly 15 years of longitudinal data to track changes over time. The survey questionnaire is rich and detailed, covering both domestic and regional issues and asking probing questions about perceptions of the economy, state institutions, and social issues. It finds continuing support for democracy as a system, with democracy preferred by large margins over an Islamic state, a military regime, or an autocratic stystem. It also finds appropriately harsh evaluations of the existing levels of democracy; the results on "ability to criticize the government", at 5.3 out of 10, is the lowest recorded since they began asking the question. Very few people say they participate in civil society or political parties.

Reporting of the results needs to be careful, as in past years, because of the weird practice of averaging of each country's results regardless of size: Kuwait, say, counts the same as Egypt, despite the obvious difference in population, which means that people in smaller states (especially the Gulf) are significantly overrepresented in the averages. Fortunately, the Arab Center breaks down the results by subregion, allowing us a better snapshot of the highly divergent trajectories of different parts of the Arab world.

And diverge they do. Unsurprisingly, perhaps, Gulf citizens are mostly thrilled: 86% say things are going in the right direction. Citizens of the Mashreq/Levant are despondent: only 39% say things are going right direction. The Maghreb/North Africa and Egypt (oddly presented as "The Nile Valley") are somewhere in the middle. The differences are as stark in the survey as they are on the ground: 94% of Gulf respondents say the economy is good or very good, while in the Mashreq/Levant only 28% say the economy is good or very good (the 4% who say very good is a nice proxy figure for corrupt elites, I suppose).

The divergences can be seen in security perceptions, as well. In the Mashreq/Levant, 53% say Israel is the greatest threat and 16% say the US (only 16% say Iran). In the Gulf, only 9% say Israel is the greatest threat and 7% say the US (only 14% say Iran) – but the most telling number in the survey in these highly autocratic countries is the whopping 42% who said don't know/decline to answer and 23% say "no threat". I would read that as their fully understanding that the mukhabarat (secret police) in their country is, in fact, the greatest threat. Everyone hates US policy towards Palestine, and US policy in general, though most (as has been the case since we began obsessively asking this question in 2001) are careful to specify that their opposition is to US policy and not to American culture or people.

Palestine remains a potent issue of shared Arab identity, regardless of the million opeds and speeches you've read saying it doesn't: 80% say Palestine is a collective Arab cause, not just a Palestinian issue – which is actually down a few points from 2012 – and almost everyone is following Gaza and experiencing it as something which directly impacts them psychologically and emotionally. Almost everyone in the region (87%) opposes normalization with Israel and only 6% accept it. Where normalization has happened, it has lost popularity: the percentage of those supporting recognition of Israel in Morocco decreased from 20 percent in 2022/23, shortly after the signing of the Abraham Accords, to 6 percent in 2024/25.

Saudi Arabia's results are fascinating, with its 62% the lowest level of opposition to normalization in any Arab country. But, again, the important number in Saudi Arabia is the 35% who replied "don't know/no answer" – which, in the context of endemic media discussions about the possibility of this extremely repressive regime potentially normalizing with Israel, seems like a pretty obvious hedging response. I'm tempted to just add the 35% to the 62% to show the real figure of closer to 97% opposition, which I suspect Mohammed bin Salman recognizes as he makes his decisions.

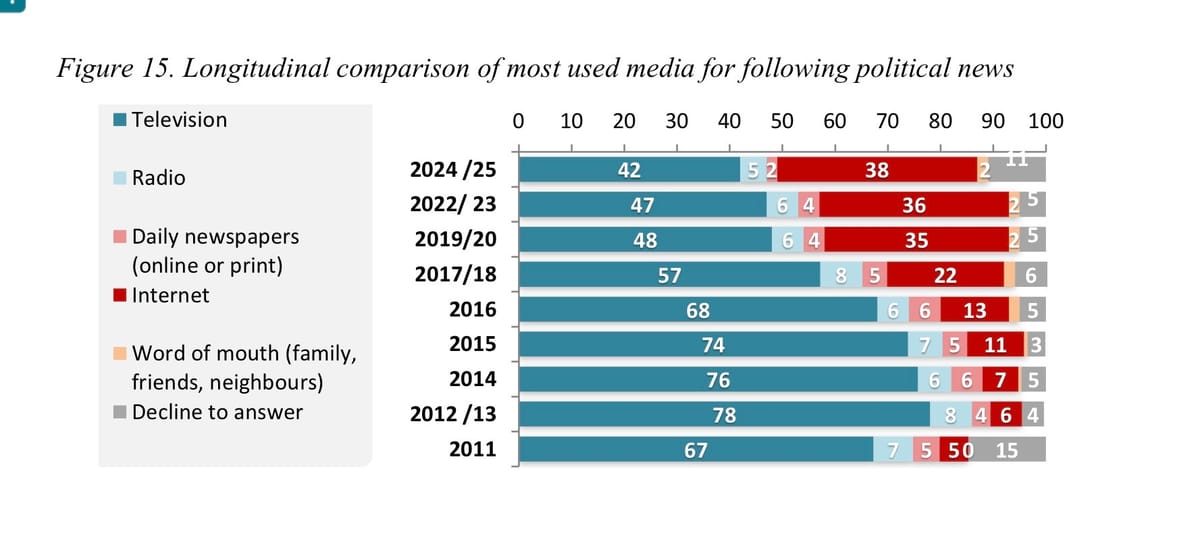

One of the most interesting questions in the Arab Opinion Index for me, as a scholar of Arab media and political communication, has always been the question about media consumption habits. The results here continue long-term trends, which when seen in the aggregate are really striking (see the image above). Satellite television like al-Jazeera is still king, but it has declined as the primary source of political news from 78% in 2012 to 47% in 2025. Meanwhile, the internet as primary source of political news has gone from 6% in 2012 to 38% in 2025. Nobody reads newspapers. There's a lot more in the survey, of course – read the whole thing here.

Arab Barometer, the other major regular high quality regionwide opinion survey, recently featured a report at the Munich Security Conference based on its ongoing ninth wave of surveys across the region. Most of the results related to the economy, democracy and other issues resemble the findings of the Arab Opinion Index, and many have already been released in other contexts. I'll just pick out one finding to highlight here: The Arab Barometer found a continuing preference for a two state solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict across most Arab countries, including 59% of Palestinians, though only 30% of Israelis and 37% of Moroccans agreed. It found low levels of support for a single binational state. Perhaps most interesting, to me at least, was what seems a high share of "don't know" respones – with the exception of Gaza, virtually every other place surveyed showed 20% or more who couldn't or wouldn't record an opinion. That ambivalence or confusion seems appropriate in this transitional moment of rampant discontent with the status quo but no idea of how to get to someplace better – a condition which applies not only to Israel-Palestine but across many of the issues facing the Middle East (and the world).

MENA Academy Roundup

Time to catch up on some recent articles and publications from around the MENA Academy.

Reconstruction and Ruin: Middle East Report 317. Every issue of Middle East Report is an important occasion in our field, and this one is no different. I find this one especially interesting since it intersects with my own current book project (more on that soon). Here is their abstract for the new issue: Reconstruction and Ruin, examines urban destruction and reconstruction as interconnected, and ongoing, processes. From the capture-and-hold strategies of militias in Khartoum to the indiscriminate use of barrel bombs in major Syrian cities, and Israel’s use of internationally supplied aerial technology to demolish cities from a distance, contemporary warfare targets civilian areas and the infrastructures necessary to sustain human life. The scale of need, the complexity of reconstruction and the intertwined character of conflict, dispossession and destruction within and between countries are without precedent and demand critical attention. What does it mean when recovery is barely finished before another wave of destruction resumes? When so-called recovery and reconstruction lead to further large-scale dispossession or displacement of civilian populations by local governments, foreign states and private enterprises? When both war and reconstruction become central means of predation and profiteering?

Contributors trace these questions across multiple contexts, following how cities are destroyed, controlled and reshaped through war and its aftermath. The pieces move between physical ruin, efforts to document and quantify damage and the financial and legal frameworks that govern rebuilding. Read together they show how reconstruction, rather than neutral or complete, is a contested process that can deepen dispossession even as communities attempt to rebuild from within. Essays include Rebuilding Gaza from the Ground Up by Minerva Fadel and Hannah Sender; Burri Under Siege—How War Remade Everyday Life in a Sudanese Neighborhood, by Niema Alhessen; The Struggle for the City—Urban Recovery and Dispossession in Mosul and Damascus by Craig Larkin; Repair Amid Ongoing Ruination—Rebuilding Dahiyeh Once More by Iman Ali; Mapping Destruction—A Conversation between Jamon Van Den Hoek and Deen Sharp; and Disarming the Camps—Palestinian Factions and the Limits of Lebanese Sovereignty, by Erling Lorentzen Sogge.

AUB's Critical Development Program has published a fascinating series of short papers. It opens with remarks by Fawaz Traboulsi, and then features a rich set of contributions: Hela Yousfi on labor protest and mining in Tunisia, Cynthia Gharios on oil, agriculture and technology in the Arabian peninsula, Jaime Allinson on Ahmed Sharaa and Syria's political economy, Joseph Daher on Sharaa's regime consolidation strategy, Zackary Cuyler on the potentialities of development in 1970s Lebanon, Lama Mourad on remittances in Lebanon's economic crisis, Mai Taha on social reproduction amidst genocide in Gaza, Mary Saba on the "housework" underpinning social movements, Nadya Hajj on digital funeral practices among Palestinians, and Roland Riachi with a critical genealogy of development in SWANA. It's an unusually rich and rewarding collection!

And now for some journal articles:

Austin Schutz, Holger Albrecht and Kevin Koehler, "The programmatic coup: ideology, the military, and political violence," Journal of Peace Research (January 2026). ABSTRACT: This article explores the effects of coup leaders' signals of ideological preferences on political violence. Leveraging a new, original data set on coup ideology, the article's findings show that successful coups d’état performed by ideologically inspired military personnel significantly increase chances for future political violence, evidenced in torture, political killings, and repression. Programmatic statements amid military takeovers of power establish expectations for future policy directions and set the stage for creating winners and losers in society beyond renegotiating elite coalitions at the time coups occur. Empirical findings provide robust support for this theory and help explain why military coups increase political violence. Understanding the logic of programmatic coups offers a valuable contribution to multiple research programs, including civil–military relations, authoritarian regime change, and political violence.

Frederick Sefton Jenkins Wojnarowski, "Hirak and Hosha: Modalities of Collective Action in Jordan in the Wake of the Arab Spring," Comparative Studies in Society and History (January 2026). ABSTRACT: This essay considers how the rural and tribal have been obscured from prevailing scholarly accounts of unrest and protest in the years since the Arab Uprisings of 2010–2012, and what this might mean for wider scholarly theorizations of protest and revolution. It draws on fieldwork in central Jordan, especially with Hirak Dhiban, where historical circumstances render visible dynamics also significant elsewhere. It takes as a heuristic binary two broad discursive modalities of seemingly dissimilar collective action that in fact reference and relate to each other in various revealing ways: on the one hand the politically populist and self-consciously leftist Hirak protest movements, prominent in the waves of protest since 2011, and on the other hosha—"tribal clashes.” It considers how contestations over the legitimacy, revolutionary potential, and moral valence of protests often hinge on discursive claims that, in a sense, Hirak is hosha, or hosha, Hirak. It engages with anthropological theories to interpret protest as a generative and affective process, rooted in local histories and imaginaries, even while responding to wider events. It calls for a broader reappraisal of where revolutionary potential is located and how it is recognized in anthropological and historical scholarship.

Jennifer Phillipa Eggert, "Challenging Dominant Approaches, Centering Marginalized Perspectives: New Writings on Gender, War, and Revolution in the Middle East," Review of Middle East Studies (January 2026). ABSTRACT: Debates on gender, war, and revolution in the Middle East are not new. The question of gender in the region has moved the imaginaries of academics, administrators, policymakers, journalists and activists throughout the decades, if not centuries. There is a similarly vast amount of literature on war and revolution in a region that has often been seen, and continues to be seen, through a lens shaped by a disproportional focus on conflict and violence. Many have brought the two perspectives together, discussing the nexus of gender, war, and revolution in the Middle East. This article is the introduction to a roundtable, which consists of three articles on gender, revolution, and war in Afghanistan, Iran, and Syria and contributes to this long-standing tradition of debates on the topic, offering unique perspectives on an oft-discussed area. Together, the three articles that make up this roundtable stand out for the broad range of their methodological approaches, their challenging of dominant approaches and simplifying binaries, and their efforts to highlight and counter the sidelining of marginalized perspectives.

Berker Kavasoglu and Kevin Koehler, "Social polarization and electoral incentives for Islamist de-moderation: evidence from Turkish parliamentary debates," Democratization (January 2026). ABSTRACT: The prospect of religious parties capturing power raises fundamental questions about the fate of secular state institutions. A prominent argument holds that participation in competitive elections incentivizes religious parties to moderate and set aside anti-systemic goals in order to maximize votes. We argue that deep-seated social polarization along the religious-secular cleavage fundamentally alters electoral incentives: when polarization is high, intensifying competition shifts the vote-maximizing strategy from centrist, broad appeals to religion-based appeals. Using a unique corpus of legislative interventions from Turkey's ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP), we scale legislators’ position on the religious – secular dimension. Exploiting cross-district variation in polarization and legislator-level differences in electoral vulnerability, we demonstrate that increasing exposure to electoral competition prompts representatives from polarized districts to adopt stronger Islamist appeals. Thus, the link between competitive elections and the incentives of religious party elites to accommodate secular institutional constraints is contingent upon societal polarization along the religious-secular divide.

Sarah Fathallah, "Algorithmic Death-World: Artificial Intelligence and the Case of Palestine," Public Humanities (January 2026). ABSTRACT: Since October 2023, residents of Gaza have been subjected to artificial intelligence (AI) target-generation systems by Israel. This article scrutinises the deployment of these technologies through an understanding of Israel’s settler-colonial project, racial-capitalist economy, and delineation of occupied Palestinian territories as carceral geographies. Drawing on the work of Andy Clarno, which demonstrates how Israel’s decreasing reliance on Palestinian labour made them inessential to exploitation, this article argues that Palestinians are valuable to Israel for another purpose: experimentation. For over fifty years, Palestinians have been rendered as test subjects for the development of surveillance and warfare technologies, in what Antony Lowenstein calls “the Palestine Laboratory.” AI introduces a dual paradigm where both Palestinian lives and deaths are turned into sites of data dispossession. This duality demands keeping Palestinians alive to generate constantly updating data for the lethal algorithmic systems that target them, while their deaths generate further data to refine and market those systems as “battle-tested.” The article describes this state as an algorithmic death-world, adapted from Achille Mbembe’s conception of necropolitics. This article concludes that as Israel exports its lethal AI technologies globally, it also exports a model of racialised disposability.